Our data says no!

Using blacklights and a specially modified camera that only sees UV light we assessed how effectively people apply sunscreen to their face. Our findings reveal that most people miss the regions around their eyes and particularly the areas near the bridge of the nose. Importantly, these regions of the face are particularly prone to developing skin cancers and our findings indicate that they are likely to be unprotected, putting people at risk.

This work has been published in the journal PLOS – you can read the primary data here (free) – or read on here for a short overview of the key points.

Why did we carry out these studies?

70 to 90% of skin cancers occur in the head and neck region and the eyelid regions along account for 5 to 10% of skin cancers. One of the reasons for so many cancers to occur here relative to the rest of the skin is that these regions are exposed much more frequently to DNA damage induced by UV light. For these reasons there is a broad push to use SPF containing creams or sprays to protect ourselves from the worst of this damage. However, these sunscreens can only work where they have been applied.

Every time we apply sunscreens we will inevitably miss patches, in this study we wanted to know how bad the problem is and, importantly, whether specific regions of the face are particularly prone to being missed.

This second point is particularly important. Cancers occur not because of a single DNA damaging event but rather because of an accumulation of multiple events in the same cells. Therefore if the same areas are always missed then the chance of critical mass of mutations occurring in one cell increase.

How did we perform our study?

We wanted to investigate how well sunscreens were applied in as normal a situation as possible. We recruited 57 people to our study and provided them with their choice of suncreams or sunsprays and asked them to apply their choice as they normally would.

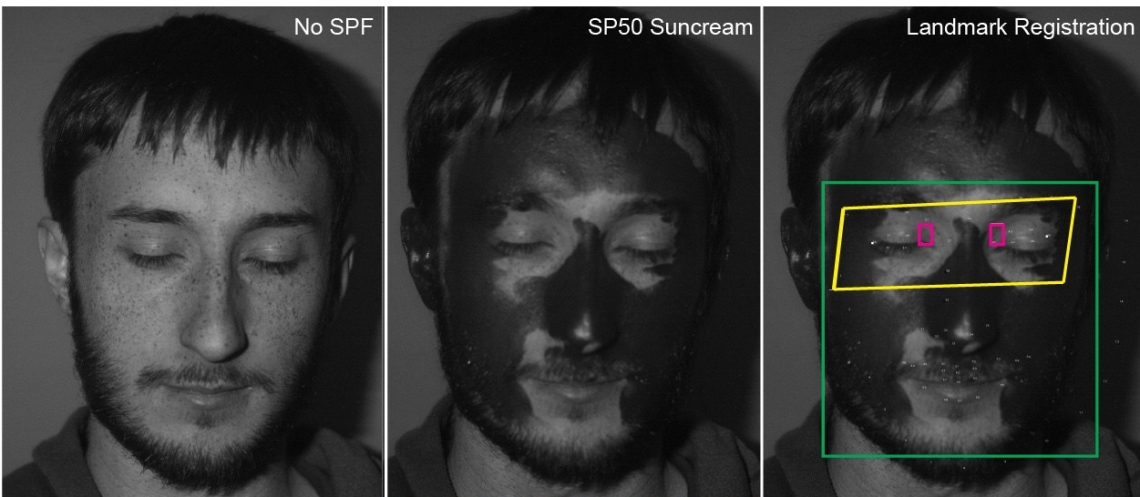

We took photos before and after applying the sunscreen using a specially adapted camera that filters out everything except UV light. As you can see from the pics, the SPF in the sunscreen absorbs the UV light and appears black on our pictures whereas the uncovered skin reflects the light back and appears lighter. Note that this imaging system also reveals non-visible sun damage and deep pigmentation in the skin – i.e. lots more freckles than you can usually see! I’ve written a short how to guide for anyone who wants to get the equipment required to do something similar.

Next we developed an automated image analysis program to calculate where the participants had covered or not covered their face.

In our pilot studies we noticed people missing their eyelid regions and so, using facial landmarks, we decided to also specifically examine these regions and also the insides of the bridge of the nose (medial canthus) as secondary questions (yellow and pink boxes in image above)

We also wanted to see if we could drive improve coverage of our volunteers by increasing their awareness of cancer risks. To do so, we invited the same volunteers back for a second visit at which time we informed them about the relative cancer incidence on the eyelid regions. The rest of the study was then repeated as for the first visit.

What did we see?

The first time the volunteers came they missed on average (median) 10% of their whole face. However, when we broke it down to eyelid and non-eyelid regions, only 7% of the facial regions not including the eyelids were missed compared to 14% of the eyelid region. In other words the participants were much worse at applying sunscreen to their eyelid regions than elsewhere.

The first time the volunteers came they missed on average (median) 10% of their whole face. However, when we broke it down to eyelid and non-eyelid regions, only 7% of the facial regions not including the eyelids were missed compared to 14% of the eyelid region. In other words the participants were much worse at applying sunscreen to their eyelid regions than elsewhere.

Looking specifically at the medial canthal areas, at the inside of the bridge of the nose, coverage was really bad with only 80% of our participants failing to cover that region.

We then invited the same people back for a second visit where we gave them a bit more information about cancer risk in the hope that we could improve these results. Coverage did improve in the second visit (down to median of 10% missed in the eyelid regions), however, in the grand scheme of things it still wasn’t great, and the medial canthus coverage was still particularly problematic.

There are some more findings including some questionnaire results in the full paper which is available here

What do these findings mean?

I don’t think anyone will really be surprised by our findings. Sunscreens sting when they enter the eyes so consciously or unconsciously we are likely to try to mitigate that risk. However, these data put numbers to the problem and it’s pretty stark.

I’d like to emphasise, the problem is not that we are likely to miss any particular area once but rather that the same areas are consistently being missed and therefore picking up disproportionately more damage than other areas. Correlation cannot prove causation however, here we do believe the disproportionately high incidence of cancer in the eyelid regions and a general poor protection in those regions are likely to be linked.

Our finding that a little of bit of information can help is encouraging and so one of the takeaways is to really try to get the message as widely spread as possible.

Conclusions

The knowledge that large area around the eyes are usually missed by most people means that we all should be extra vigilant when applying sunscreens. Realistically, the fear of getting sunscreen in your eye means that we should really look to other mechanisms of protection therefore we strongly recommend actively UV protective sunglasses and wearing a hat.

What next? Getting the message out there!

This was a relatively simple study but we think it has an important message. Please share the knowledge as widely as possible.

Since carrying out this study we have run public engagement events at local museums and hospitals (you can read our blog posts about these events here and here) and filmed with ITV and BBC and the press release was carried in lots of newspapers and magazines, some links to articles in skiing magazines here.

If you would like any more details please get in touch, one of the study authors would be happy to respond or if you want details of how to do this stuff check out our how to guide.

left, without sunscreen, middle visit 1, right visit 2

About the authors

Kareem Hassanin, performed these studies as part of a MRes in Clinical Sciences. He designed the questionnaires, performed the participant recruitment, acquired the images. Harry Pratt and Dr Yalin Zheng, are image analysis experts in the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool. They wrote the code that converted the photographs into quantifiable data. Dr Gabriela Czanner is biostatistican also based at the University of Liverpool. She was instrumental in study design and guided the statistical analyses. Dr Kevin Hamill and Mr Austin McCormick jointly conceived, designed and supervised this project. Kevin is a faculty member in the Department of Eye and Vision Science in the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease. Austin in a consultant ophthalmologist and oculplastics surgeon who regularly deals clinically with eyelid tumours.

Footnotes

The camera we used was a Canon DSLR (this is an amazon affiliate link but we actually used a relatively old second-hand camera) equipped with a 60mm EF-S macro lens (we used f3.5, shutter speed 0.8s, you are working with quite low light from the LEDs!). The camera was modified to only see UV by lifepixel who replaced the internal hot mirror with a UV band pass filter. Conversion currently costs $475 dollars.

This sort of research is easy to perform and could make a science project for schools, undergraduates etc. If you want advice on how to set anything up, you can contact us via the form below. Similarly, if you would like us to visit your school or other group setting you can contact us via the form below.

Conflicts of interest (None!)

This research was performed by researchers in the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool and NHS teaching hospital at Aintree Liverpool. None of the team have every received any products, money or other remuneration from any camera, lighting, sunscreen, or other related companies. We do not endorse any products. We specifically want to stress that we performed this study as we thought it important than an independent group of researchers provided the evaluation.

Participants in the study were recruited from students and staff at the University of Liverpool. They received remuneration for taking part but were not informed of the purpose of the experiments nor shown the images until after the study was completed. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Liverpool ethical review board.

Our equipment was purchased thanks, in part, to a Wellcome Trust Institutional Grant and through funds received directly from our research institution. The links above are provided for reference only. Please be aware that if you purchase products from amazon after arriving at their site via those links then we will receive a small percentage for referring you (usually 4%). Any money obtained through this mechanism will be used to buy supplies for our public outreach events such as photo paper and print cartridges.

5 Comments