It’s not everyday I get to write a title like that ^^. Indeed, this is the most exciting imaging journey I’ve ever been able to report on. This is part 1 of what is likely to become a multipart blog record of our adventure in iPALM super resolution imaging.

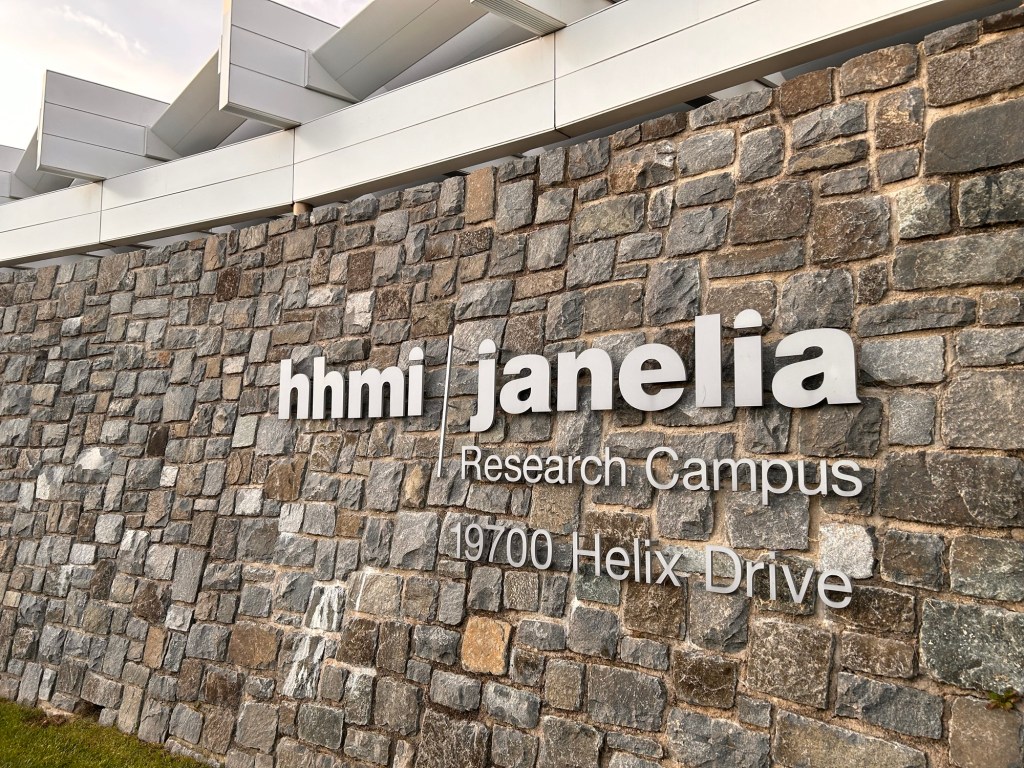

Late last week Natasha Chavda, Tom Waring and I travelled to Janelia Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Research Centre just outside Washington DC. A beautifully lush research campus dedicated to research mostly with a biological slant. Oh, it also has amazing research facilities and equipment.

We’re here as we applied to use a microscope here that isn’t available anywhere else in the world, to answer a question that therefore couldn’t be answered anywhere else in the world.

Super resolution microscopy

Right, regular readers of this blog will be aware of my general love for microscopy. Images at the top panel, footer, sidebar and previous posts (links) showcase some of the cool images that have come from my team over the years. For most of those pics we have used antibodies to localize the proteins we were studying and then used lasers to excite the fluorophores attached to those antibodies. By shining the lights through a pinhole we are able to remove some of the out-of-focus light and generate an image that is of a single plane. This is called confocal microscopy, it’s great but it has its limits.

The ability to determine if a point of light comes from one thing or two things is resolution. For light microscopy, including the confocal microscopy we routinely do, the resolution is limited by a number of factors relating to the physics of photons and also by the labelling density of either the antibodies or fluorescent proteins used.

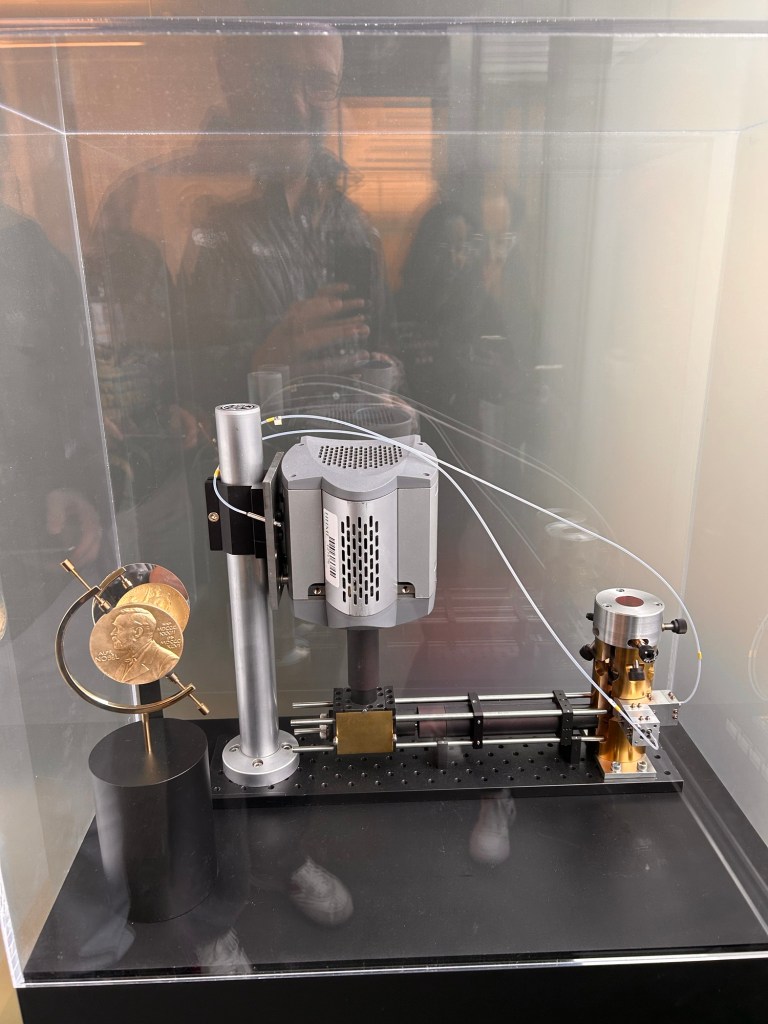

To resolve further than possible with light microscopy requires a way to light up individual proteins one at a time (we call this blinking) and some complicated physics and maths. Complicated enough that the Nobel prize was awarded for this in 2014… here’s a picture of that medal, Eric Betzig works at Janelia. You can read about the story behind that Nobel here; it’s pretty awesome.

The Nobel prize was awarded for a type of super resolution microscopy called PALM – photoactivated localization microscopy – the photoactivated bit referring to using light (lasers) to turn on individual fluorophores. PALM is amazingly cool. Now you can buy commercial microscopes that have PALM capabilities, we have one at the University of Liverpool and Natasha and Tom were doing some of that before we came here. PALM is really good for axial resolution (X vs Y) but where it is limited is determining depth (Z).

iPALM

What we are doing here is an advancement on PALM called interferometric PALM (iPALM). And this is mind-blowing. The theory here is that if you image the same photon from two directions simultaneously then overlap the waves from multiple defined proportions then you can backwards calculate the location in the Z plane. Diagram below if that helps.

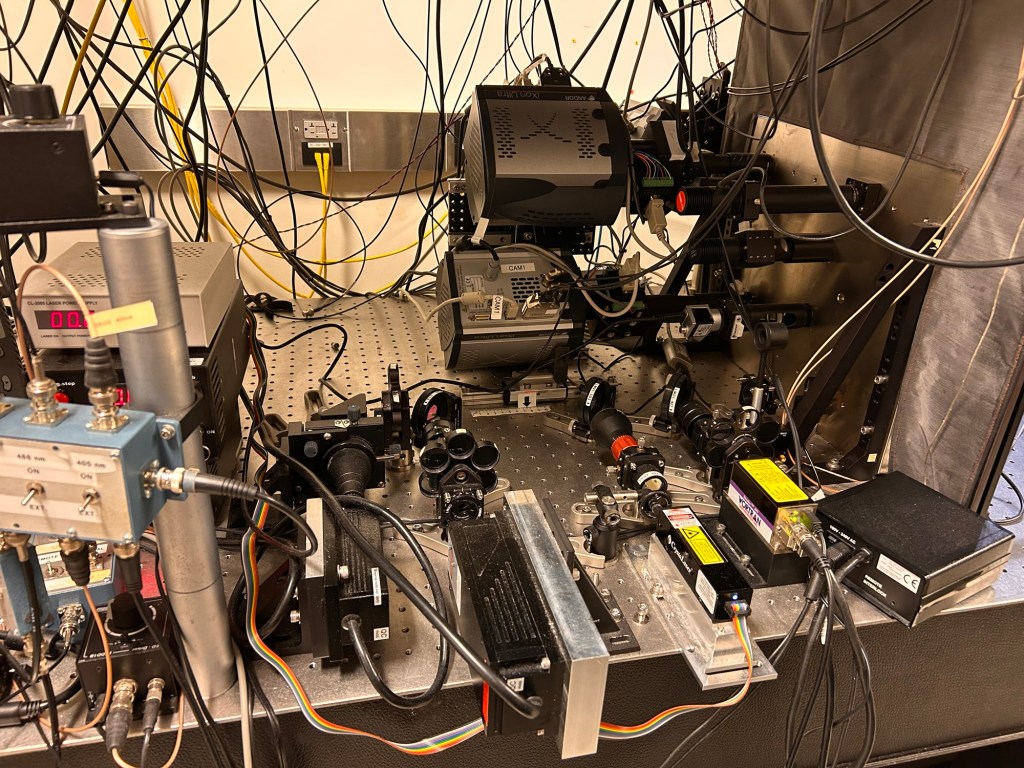

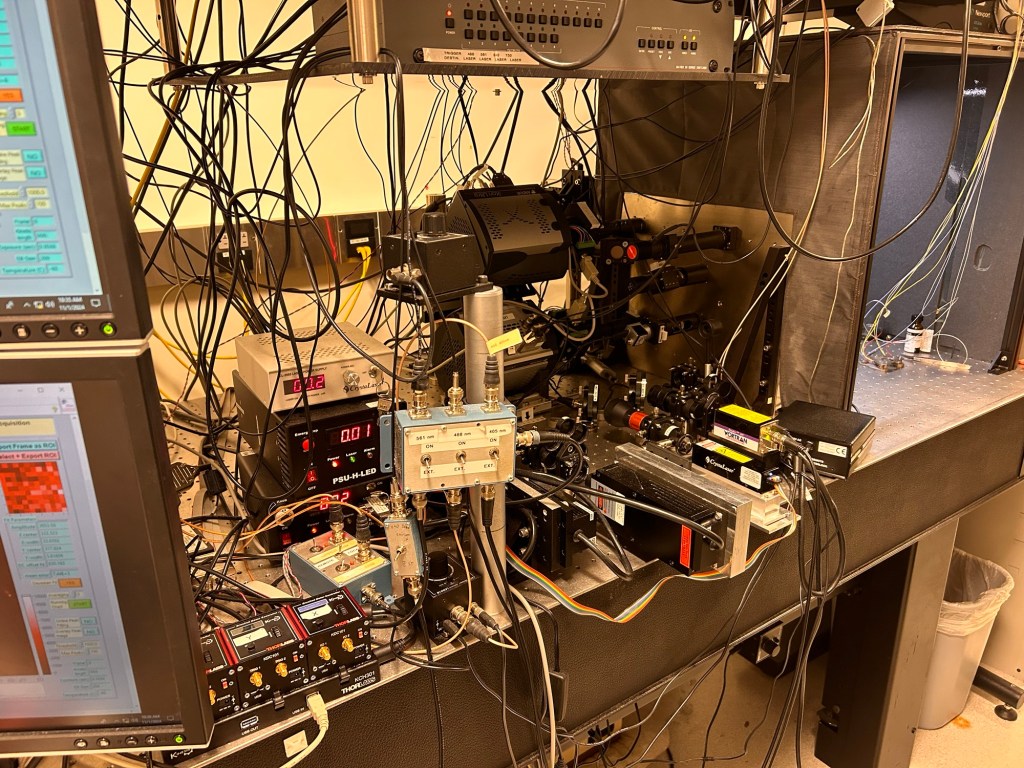

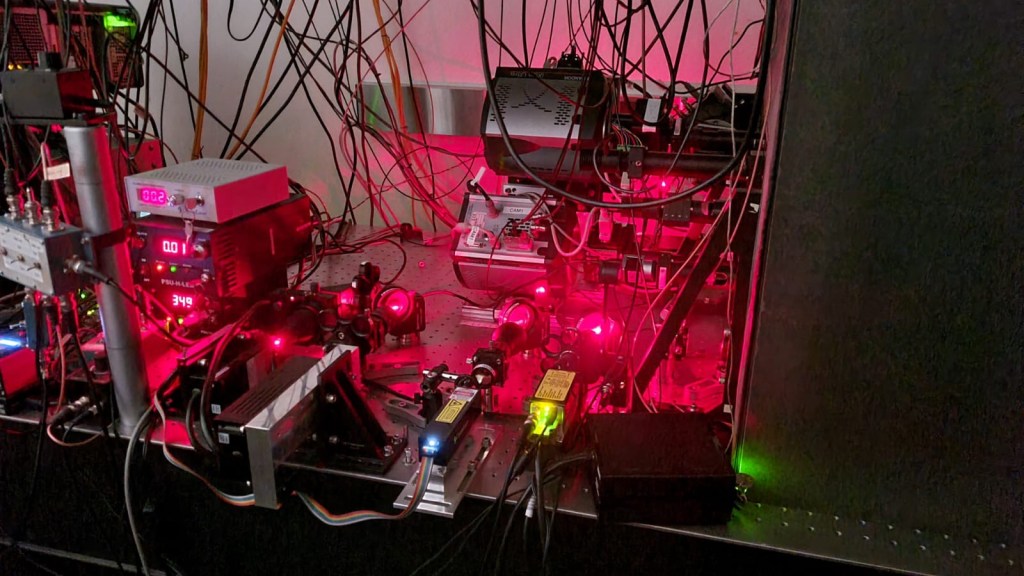

To do that though, you can’t just ask one of the big microscope companies to send you an (expensive) box ready to go. Instead you need to design and then custom manufacture the beam splitter and assemble all the other bits, align everything and do some magic. Hence this crazy complex assembly you can see below.

As with all things science, the experiments are about the optimization. Over the next few weeks we will be trying to get our conditions right so that the fluorophores blink at the appropriate density and brightness so that we can go on to collect the data. The last few days we’ve been tweaking our staining conditions then imaging then tweaking, then imaging. Danger: PI in the lab.

Once we get the conditions right, we anticipate generating 100,000 images per colour per cell to generate the final picture of what is going on. 2 cells per day, maybe 3.

Look out for update 2 once we have something to update. Hopefully.

3 Comments